- So you want to know about a group, eh?

- So I promised you symmetries…

- Some neat little proofs

- So I promised you symmetries (part 2)

- A distraction: infinite groups

- New groups out of old part 1: direct products

- So I promised you symmetries (part 3)

- Observations about the symmetric groups

- Working with Cayley tables

- What do I mean by ‘same’?

- A note on isomorphisms

- More on homomorphisms

- The sign function of the symmetric group

- Computing the sign of a permutation

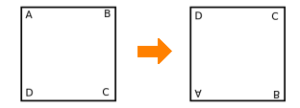

Recall our example of the rotations of a square:

At the end of part 1, I asked where we’d seen the infinite cyclic group before. It actually had the same structure as the whole numbers with addition. This is why we don’t talk about the group C∞ as we already have a name for it. I’ve neglected to mention that the set of whole numbers are called the integers, and are denoted by . Since

doesn’t form a group (why? have a go), we often use

as shorthand for

. Anyway…

The family’s getting bigger! Dihedral groups. You may have noticed that there seemed to be some natural configurations of the square missing. Or that I kept on talking about rotational symmetries. Well we can use groups to work with the reflective symmetry of regular polygons too. And that’s the aim of this post.

So what was missing? Well, we have some reflections. Before I go through them, see if you can get them all.

We have,

So, together with the rotational symmetries we saw in the last post and the ‘do nothing’ symmetry, we have 8 symmetries for the square.

Before continuing: by using these pictures or your own, write down the Cayley table for this group. This might take a while, but is well worth it. Spoiler: be careful with the order you are doing things! Remember red then blue. You could also do this for other n-gons.

Now a sensible question (who would call any maths question stupid anyway?) would be whether this is a group we have seen before. We have 8 symmetries. The only group we’ve seen so far that contains 8 elements is C8. I can think of three ways to see that these are not the ‘same’ (i.e. isomorphic, a term we’ll come to in another post. Just think of isomorphic groups as being of the same order and having the same way of combining elements or, for finite groups, the Cayley tables of the groups being identical except for the letters used). Before continuing, ponder why they’re different. You may find the points below helpful with this.

- What was the definition of cyclic? Could it be that the group of symmetries of a square is cyclic?

- The order of composition for Cn did not matter, is this true for composing the reflections and rotations of a square?

- What are the orders of the elements of C8?

Just so we’re clear, these are not the same. The 3 ways I was thinking of seeing this were:

- The definition of cyclic was that we could generate (think: get to) every element of the group using one symmetry. So to generate C8 we would require an element with order 8. From the Cayley table, there is no element of order 8.

- Composing a clockwise rotation of 90° and the first reflection shown above provide different symmetries depending on the order that they are composed. Hence this is an example of group that is not commutative and different from C8.

- In order for groups to have the same structure, a necessary condition is that they have the same number of elements of the same order. Note that this is not a sufficient condition e.g. there are two groups which both have 27 elements, an identity and 26 elements of order 3, but where one group is commutative and the other is not.

Before I introduce the family, it’s well worth seeing what you can discover for yourself. Look at the symmetries (rotations and reflections) of n-gons for small values of n. Note that we are only keeping track of where the vertices A, B, C, and D are sent. Before continuing: make a prediction of how many reflections there are for an n-gon. Geometrically, is there a difference when n is odd or even?

Right! Looking back at our example of a square we have two reflections which move all of the points, with one being

and the other with a horizontal line. We also have two reflections which fix two points and permute the other two points, one going through the vertices labelled B and D and the other being

This means that for a square, our line of symmetry either goes through 2 vertices or through 2 edges. Any n-gon where n is even continues this pattern: half of the lines of symmetries pass through two vertices and half of them pass through two edges. When n is odd, an n-gon will have all of its lines of symmetries going through an edge and the opposite vertex. Thus for any n≥3 we will have that there are n reflections of an n-gon.

The symmetries of a square (a 4-gon) defined above form the group I will call D4, a group of order 8. In general, the symmetries of a regular n-gon then form the group Dn, which has order 2n. Notice that D4 contains all of the symmetries seen in C4. Because all of the elements of C4 lie in D4, we can say that C4 is a subset of D4 and denote this by C4 ⊆ D4. Since this subset forms a group, we say that C4 is a subgroup of D4, denoted by C4 ≤ D4. Notice that, for all n≥3, we have that Cn ≤ Dn. We will see more examples of subgroups in part 3.

Definition Let (G, ×) be a group. If H is a subset of G and (H, ×) is a group, we say that H is a subgroup of G, denoted H ≤ G.

Before continuing: work out the orders of elements of Dn for small values of n.

Is this a new family? In contrast to the cyclic groups, we noted that D4 is not cyclic: it cannot be generated by one element. We know that, in general, Dn consists of the rotations forming the group Cn and n reflections. What can we say about the order of the elements of Dn based on this observation? Well, none of the rotations can have order greater than n: doing so would mean they generate a cyclic group with more that n elements. Also, the reflections must all have order 2. So Dn is not cyclic for any n≥3.

Generating Dn for n≥3. If we cannot generate Dn by one element, how many do we need? I’ll give you some hints but it really is worth having a go yourself. The first observation that I’m going to use is that we can pick a rotation -let’s call it r– which will generate all of the rotations of Cn, from the fact that these groups are cyclic (note that not every rotation will do this in general). Now it really is worth you having a play.

Before continuing: draw a labelled n-gon (either for a general n or by choosing a small value for n). Combining powers of r with a single reflection, which reflections can we get? What about combinations such as reflection then rotation then reflection?

The answer? It really is worth trying for yourself, so I’ll just say that it suffices to use any reflection -let’s call it s– and the rotation r to produce all of the elements of Dn. This means that we can say that Dn is 2 generated: all of its elements can be produced by using just 2 elements. You probably found some strange relationships between the reflection and rotation, so we’ll get onto that next. Again, see if you can do this yourself. Specifically, can you come up with a way of getting from one reflection to any other one? Try working out, for any rotation d, what sds and dsd do.

To algebra! An algebraic viewpoint. We’ll start with our first example of a group, . If you wanted to tell a computer about the structure of this group, what could you say? What do we know about it…it can be generated by one element, and it is infinite. The Cayley table would look very repetitive indeed. So we’ll tell it that only one element is needed to generate it -let’s call it r for now- and that there are no conditions on the element r: for no non-zero power is it equal to the identity. We therefore can write

as

.

Here, the left part says what generators we are using, and the right part tells us what relationships these generators satisfy. I am being vague, since this can quite easily get very technical. Another example? Each finite cyclic group can be defined using a single generator which has a condition that a power of it is equal to the identity, i.e. Cn can be written as

.

Finally, we have our dihedral groups. Again we know something about these: they can be two generated by a rotation, r, and a reflection, s. So we need to tell our computer about r and s algebraically. First off, we can say that the rotation has order n, in the same way we did for Cn. We can also say that the reflection has order 2. But how do r and s interact? Above we investigated what srs produced. The answer was that this was the inverse of r, denoted by r-1. This is enough detail so that the computer knows that we are talking about Dn and not another group. Hence for any n≥3, we have that Dn can be written as

.

This way of writing a group is called a group presentation.

The rest of the family. For completion, I will now define D1 and D2. It is worth noting that, to my eyes, there are two ways to do this: from the geometric intuition we have built up (we could look at the reflective symmetry of a point and a line) or the algebraic structure of the Dihedral groups. Following the geometric intuition provides a different answer to that conventionally used for these groups, which is to just extend our algebraic definition of Dn for n=1 and n=2. Using the same structure as above we have

Notice that the first presentation can be simplified since r has been defined to be the identity (r=1 is a relation shown on the right). See if you can work out the structure of D1 (answer here) and also whether or not D2 is commutative (what tool could we use to help with this?).

As a final comment, there are two notations for the meaning of the subscript of Dn. See wikipedia for details. See you next time for the final part on symmetries!

I have heard about a group called the “MONSTER GROUP”! Is the monster group the group of symmetries of something?

LikeLike

Could you write a post about this Dr Tait? I will aim to introduce these when I get to finite fields…remind me if I forget!

LikeLike